Implementing your presenter with Rx or Functional Reactive architecture for Android applications

It is pretty common to implement data layers with Rx: just glue some requests together with merge() or concat() and subscribe to the result. It is less common to implement presentation layers (presenters or view models) with Rx. And that is surprising, because a presentation layer is just the type of system Rx is designed for. It is an asynchronous processor — it receives asynchronous signals (user clicks, network responses, or system events), processes them, and emits asynchronous signals back (view updates mostly).

This sounds good in theory, but does it work in real life? The only way to answer that question is to try this approach on a live application with requirements coming from real business needs. I had an opportunity such as this, and this article is about what came out of it.

This approach starts to gain traction slowly; if you have heard the words MVI (Model View Intent) or MVVM with Rx, this approach is the same. But back then these words were not googlable yet, so it was a surprise for me that the thing actually worked. And not just worked, it felt like a long-lost, true way to implement UI. The traditional imperative approach with stateful presenters or view models was starting to feel synthetic and overcomplicated. I had a similar feeling when adopting functional programming after years of Android Java.

Presenter is a function

I start my journey with a good old class Presenter, and I just try to implement its guts with Rx. Eventually, it becomes obvious (and it was quite a surprise) that the class itself is no longer needed. It looks like the presenter is trying to take this form:

fun present(/* input streams (observables) */): ViewModel {

// ...

}

This is a function. What does it do? Well, it transforms a bunch of observables into another bunch of observables.

As input, it takes observables with user interaction events; a click on a button is an example of such an event. It is easy to construct an observable that emits an item each time the event happens. Another example is an observable that emits a string each time a user types something in an input field.

fun present(

updateButtonClicks: Observable<Unit>,

passwordEditTextChanges: Observable<String>

): ViewModel {

// ...

}

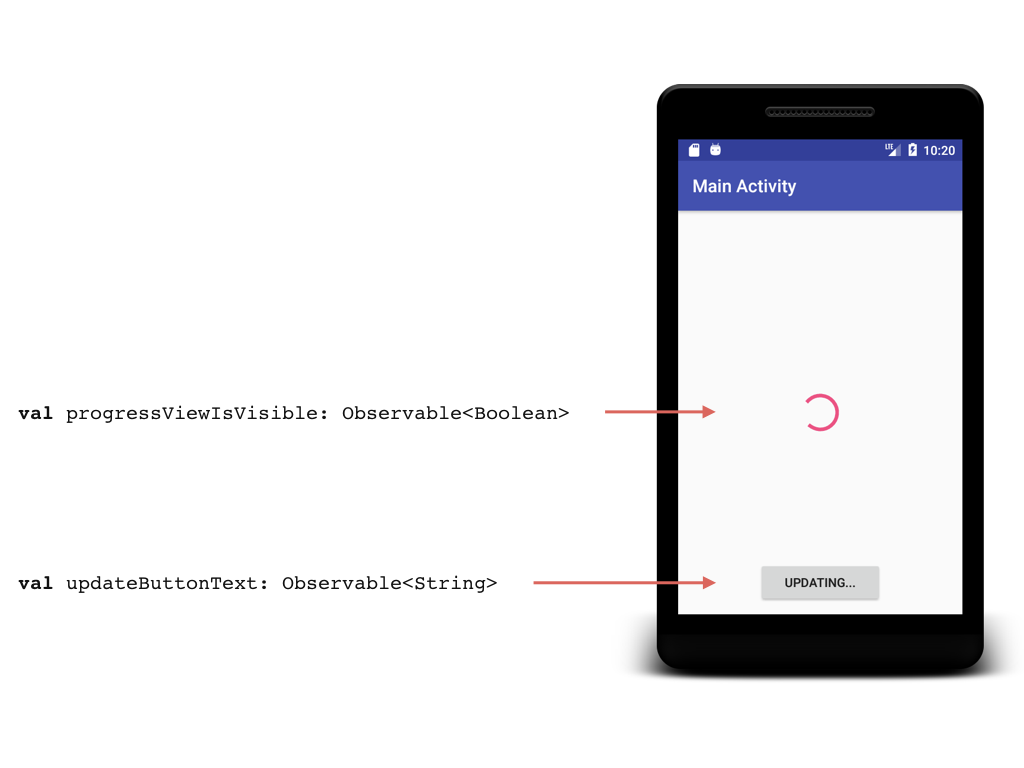

An output of this function is an instance of a ViewModel object, which is just a container for a bunch of observables with view states. A view state is some property of a view, like visibility, margin, or button text:

data class ViewModel(

val progressViewIsVisible: Observable<Boolean>,

val updateButtonText: Observable<String>

)

Here are those properties on the screen:

Activity can subscribe to these view states and map their values to corresponding view properties:

viewModel.progressViewIsVisible.subscribe {

progressView.visible = it

}

viewModel.updateButtonText.subscribe {

updateButton.setText(it)

}

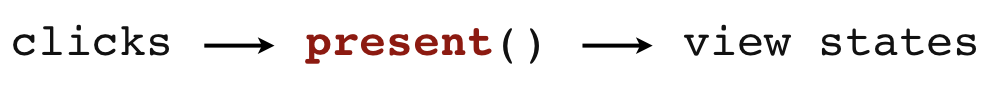

So, to sum this up, present() is a function that transforms streams of clicks and other interaction events into streams of view states:

This is what the typical activity looks like with this approach:

class MainActivity : Activity() {

override fun onCreate(savedInstanceState: Bundle?) {

/* ... */

val viewModel = present(/* input streams */)

render(viewModel)

}

}

Yes, it is that simple. Activity’s role is just to resolve dependencies for the present() function and to provide an entry point to start the whole process.

Implementing present() function

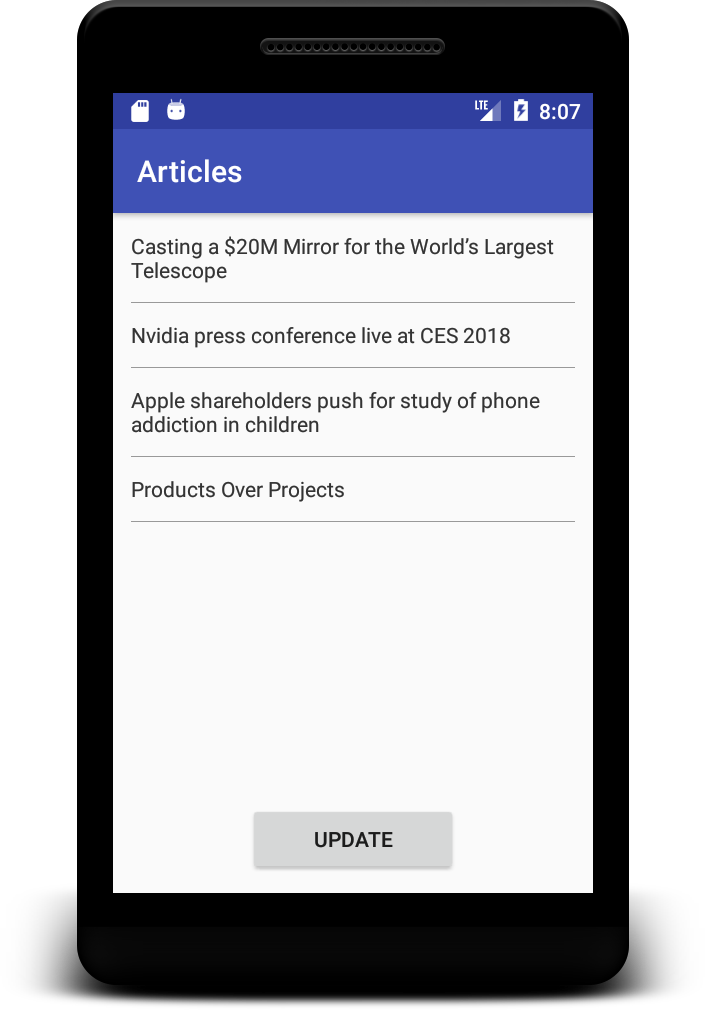

present() function is the heart of the activity. It owns all the complexity and all nontrivial presentation logic. How is this function implemented? Let’s see that on an example of this activity:

This is a screen with an “Update” button; each time we click it, a new list of articles is downloaded from the server and displayed on the screen.

How do we implement this? As an input, we expect to have a stream of button clicks and something that can download articles for us (call it ArticlesProvider):

fun present(

updateButtonClicks: Observable<Unit>,

articlesProvider: ArticlesProvider

): ViewModel {

/* ... */

}

We combine these two inputs into an observable that downloads and emits a list of articles every time the update button is clicked:

val articles = updateButtonClicks

.flatMap { articlesProvider.getArticles() }

Suppose activity knows how to “render” these articles (by passing them to a proper RecyclerView adapter, for example). We then consider this observable a view state, and final implementation of a present() function looks like this:

fun present(

updateButtonClicks: Observable<Unit>,

articlesProvider: ArticlesProvider

): ViewModel {

val articles = updateButtonClicks

.flatMap { articlesProvider.getArticles() }

return ViewModel(

articles = articles

)

}

It’s funny how this resembles an ordinary presenter, but look at the articles observable again:

val articles = updateButtonClicks

.flatMap { articlesProvider.getArticles() }

This expression defines a rule for how to compose articles view state. To define another view state, just create a new rule and place it, say, below the previous one:

fun present(

updateButtonClicks: Observable<Unit>,

articlesProvider: ArticlesProvider

): ViewModel {

val articles = updateButtonClicks

.flatMap { articlesProvider.getArticles() }

.publish().autoConnect()

// This is the new view state.

// It controls visibility of an “empty state” view

// which is visible when there is no articles to show

val emptyViewVisibility = just(true)

.concatWith(articles.map { it.isEmpty() })

return ViewModel(

articles = articles

emptyViewVisibility = emptyViewVisibility

)

}

And this is what the work process looks like. We identify view states we need to implement, and then we write a rule for each of these view states and place these rules one after another. At the end, the present() function is just a list of view state definitions. It may contain other stuff, of course, like definitions of observables, which are used in the construction of several view states, but mostly the present() function is just a list of view states.

Here is an example of how a

present()function may look like at the end

Compared to a traditional presenter, this form feels very… unentangled, and this affects how quickly a solution’s complexity grows. My general feeling is that with a traditional presenter, the complexity of a solution increases as a square of the complexity of the requirements. Each added requirement tends to affect several pieces of code, and so, the more code you already have, the bigger are the complexity increases after each update. With the Rx approach, it feels like updates are usually much more isolated and the complexity of the code is more like of linear dependency on the complexity of the requirements. This means that the bigger and more complex your activity is, the greater the advantages of implementing your presenter with Rx. With the simplest activities, it feels like the complexity of both solutions is nearly the same.

Why complexity matters

It’s not hard to illustrate what this decrease in complexity gives a developer. Imagine you revisit your code after a while. Perhaps it’s time to change how one view state works or to fix a bug in one of them. To change something, you need to understand it first. Now, you probably click on a variable or a function responsible for this view state and browse through the entire huge presenter to see where the thing is used and how it mutates. You build a mental model in your head. The problem is that this mental model is pretty unstable. If a colleague comes to your desk and asks something, the model is broken and you have to build it again. With Rx presenter, it’s pretty cheap to rebuild the model. All necessary parts are there in one place: the place where the view model observable is defined.

Now, imagine how much simpler it is to modify this kind of code — you can see immediately what your changes will affect and what they will not. You can be sure that you are not introducing a weird bug by manipulating some shared state in an unexpected way, because all state mutations are restricted to a single place, to the place where the corresponding observable is defined. You can grasp everything that happens with a state with a single look.

The true form of a presenter

Now I want to share another exciting thing about this approach. This insight comes from André Staltz’s talks and MVI documentation from the cycle.js site. Look again at our activity:

class MainActivity : Activity() {

override fun onCreate(savedInstanceState: Bundle?) {

/* ... */

val viewModel = present(/* input streams */)

render(viewModel)

}

}

The onCreate() function serves the role of a main entry point — it’s like a main() but for an activity. With this in mind, we notice that the code above resembles this:

fun main() {

render(present(userInput()))

}

What does this mean? We just took our super complex activity, which consists of a view, presenter, and asynchronous events of all kinds, and turned it into a composition of three functions. Each function has a deadly simple meaning. Our program suddenly becomes so simple and so easy to think about. Maybe this is the natural way UI programming should be done?

And look at the presenter. It was an abomination with a hard-to-grasp role and a potentially incomprehensible knot of states inside. Now it is a transform function that is simple and elegant. It feels like the presenter’s true form; it was hidden all these years in a pile of OOP boilerplate, and Rx with FRP just helped reveal it.

I am pretty convinced now that FRP is the natural way to write UI applications. From what I have seen so far, it is better than the traditional imperative approach in all aspects. It feels like the programming paradigm of the future.

GitHub repository with an example project